Chenkoush – Games

Author: Lory Tashjian, 24/12/2022 (Last modified: 24/12/2022) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

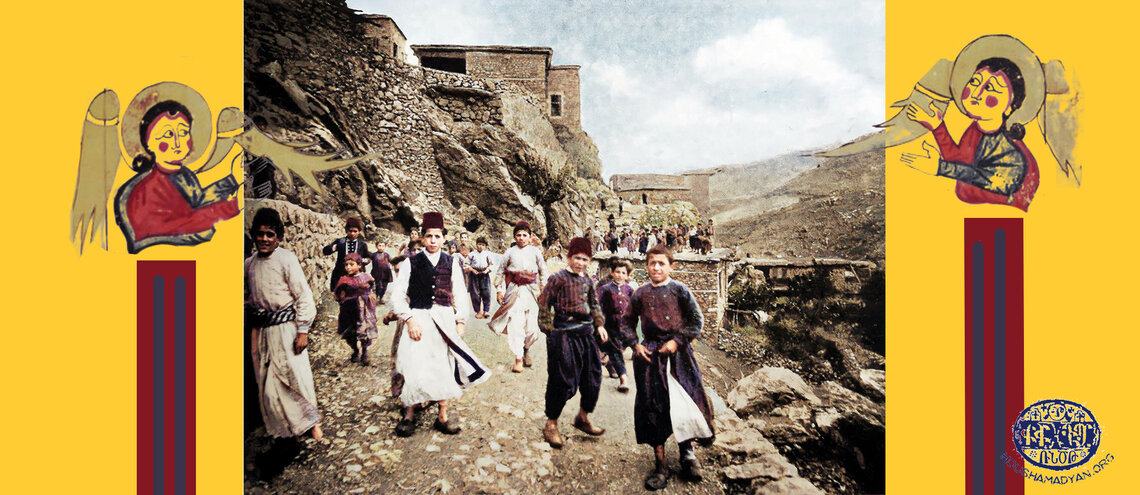

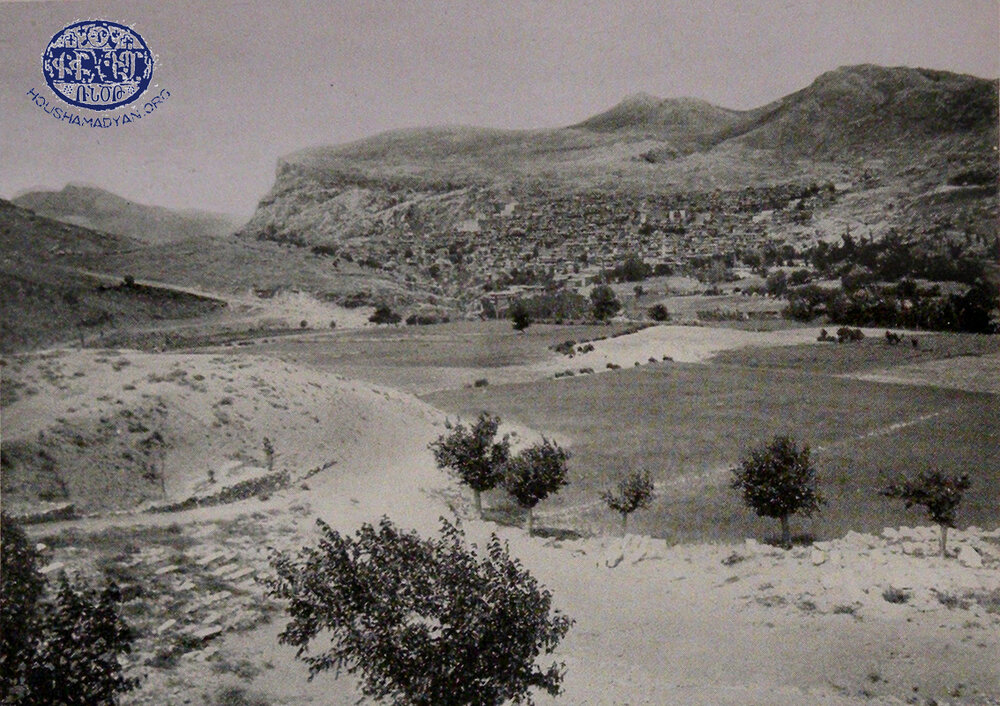

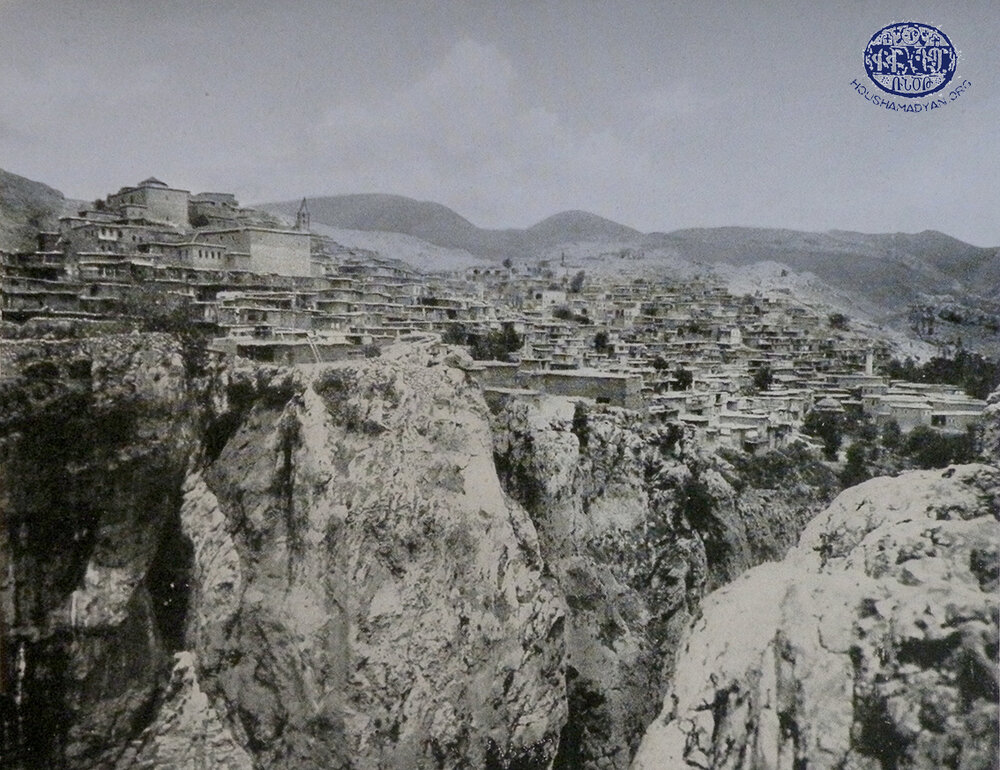

Chenkoush (present-day Çüngüş) was an Ottoman city with a majority-Armenian population. It was built on rocky ground, at an altitude of 1,049 meters above sea level. The city was part of the province (vilayet) of Diyarbekir, and was located northeast of the city of Diyarbekir, south of Kharpert (Harput), and north of Siverek. The Euphrates River flowed to the west of Chenkoush.

Like in other Armenian-populated cities and villages across the Ottoman Empire, the Armenians of Chenkoush had developed unique local customs and traditions, which were described in later years in the writings of natives of the city living in the diaspora. These descriptions served as the primary sources for the information provided in this article.

Traditional games are an inseparable component of our ancestors’ heritage. They are manifestations of lifestyle and customs, often tied to local beliefs and inspired by local traditions and ceremonies.

This article is an attempt to describe the children’s, adolescents’, and youth’s games played in Chenkoush. The information provided in this article is mostly based on the book Chenkoushabadoum [History of Chenkoush] by Karnig Kevorkian (Jerusalem, 1970).

The area’s traditional games had simple and easily comprehensible rules, as well as a unique lexicon associated with them. Specifically, the following three terms were commonly used in both individual and group games:

- Mar: In the local dialect, the word meant “mother.” The mar was usually designated by lot at the start of a game. The mar would be the game leader, especially in the case of games played by a large number of players. He/she would have special privileges not enjoyed by other players.

- Bargogh (either an individual player or a team, depending on the game) [the player bending or lying down, the “it”]: The losing player or the player at a disadvantage.

- Hel [goal]: The goal or target, which a team or both teams attempted to reach or gain. The hel was determined or defined by the members of both teams (or both players) at the start of a game.

These terms were used as components of longer phrases that were commonly employed during games, including:

- To score a hel: To reach the target or the goal; to score; or to win the game.

- “Mor haram chullar!” [The mar cannot be haram]: As we noted above, the mar enjoyed special privileges. This expression meant that the if the mar committed a foul or irregularity, he/she would not be penalized and would not have to be the next bargogh in the game, unlike the other players, who would incur a penalty for the same transgression.

- To walk under the loudz [yoke]: The players on the winning team would stand in two lines, facing each other, and hold each other’s hands, thus creating an arch-like passage between them. The players on the losing team would have to hunch their backs and cross this passage. If the game involved few players, or only two, the losing players would have to carry the winners. Upon being lifted by a losing player, the winning player would cry out, “Bring me a midwife, and I’ll bring you a calf!”

- Prnvogh [Captive]: A player who was eliminated from a game. [1]

Occasionally, with the agreement of all the players involved, a referee would be appointed to oversee a game.

Badjilar

This was the most popular game played in Chenkoush. It was usually played by adolescents, and sometimes also by youth.

The bargogh would lean forward, bending at the waist. He/she would spread his legs and hold his/her knees with the hands. The other players would line up a predetermined distance, run at the bargogh, place their hands on his/her back, and leap over him/her. After each round of leaping, the bargogh would raise his/her back and waist slightly. Eventually, the bargogh would completely straighten his/her back, and stand with only his/her head bowed. In other words, the other players would have to leap over his/her entire length.

The first leaper would always be the mar, who would take a running start, place his/her hands on the bargogh’s back (and later in the game, on his/her head), and leap over. As he/she leapt over, he/she would say, “Mor haram chullar!” This invocation meant that the mar was exempt from being eliminated and would be allowed to continue playing even if he/she failed to make the leap. But in the case of the other players, if their leg or backside made contact with the bargogh during the leap, or if they simply fell atop the bargogh, they would lose and would assume the role of the bargogh. The previous bargogh would become the new mar, and the previous mar would be the last leaper.

As he/she leapt, the mar would recite a different quatrain each time, consisting of nonsensical phrases in Turkish. Each of the other leapers had to repeat the rhyme. With every leap, the mar could invent a new quatrain. One such quatrain was:

Badkilarin badjisi

Ichinde var adjisi

Ana kalk pilav boushour,

Santour santour gel otour. [2]

Translation:

Sister of sisters

Feels pain inside of her

Mother, rise and cook some rice

[Unintelligible] come and sit.

Ara Badjilar

This was a non-competitive, fun game. The bargogh would lean forward, bend at the waist, spread his/her legs, and hold his/her knees with the hands. The second player would leap over the first, and then assume the same position a few meters ahead of him/her. A third player would leap over the first two and then assume the same position a few meters ahead of the second player. This process would continue until all the players had a chance to participate. Then the cycle would begin again with the first bargogh leaping over all the other players and then assuming the position of the bargogh again.

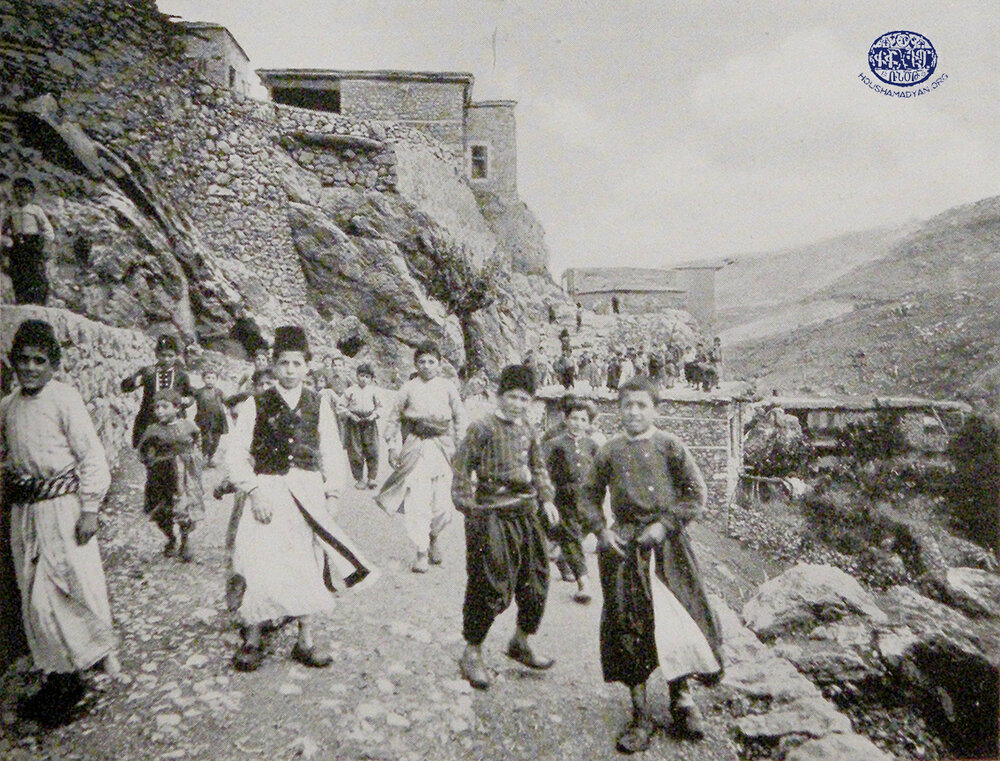

In Chenkoush, schoolchildren would often play ara badjilar on their way home from school. [3]

Agha Toura

This was a relatively rough game. It was often played by youth during Easter celebrations in the Armenian cemetery, located west of the city. Turkish youth would also participate in the game.

First, a player would be designated as the agha and another as the gelin. These two would be teammates. All the other players would be on the opposing team. The game was more enjoyable with a larger number of players.

A circle with a diameter of three meters (ten feet) would be drawn on the ground, and the gelin would sit in the center. He/she would hold a rope measuring 1.5 meters (five feet) in length. The agha would hold the other end of this rope. In his/her other hand, the agha would hold a whip.

The other players, all on the opposing team, would attempt to enter the circle and strike/tag the gelin. Meanwhile, the agha, without letting go of the rope (in other words, without leaving the circle), would use the whip to ward off the attackers. But while the agha was busy, a good player could jump onto his/her back and sever the link between him/her and the gelin by forcing him/her to let go of the rope.

Many players would receive injuries from the strikes of the whip or from kicks received while playing this game. [4]

Kalakousha (Fort Game)

Strong youth would play this game, especially on Red Sunday, which coincided with the last Sunday of the Easter season (the fourth Sunday after Easter). The game was played in the evenings, in the Armenian cemetery of Chenkoush.

Ten to twelve youth (and sometimes more) would line up, lock arms, and then kneel. A smaller group of eight to ten youth would line up behind the first group. Each of them would climb onto the shoulders of the two participants in front of him. The kneeling youth would then stand, also raising those standing on their shoulders. This was the kalakousha, a type of dance.

Attempts were sometimes made to add a third row of youth on top of the second one. If they succeeded, the dance would continue, with the participants forming a three-story fort. [5]

Salapkar

In Chenkoush, the salapkar was a rock located between the Armenian Apostolic, Catholic, and Protestant schools. These three schools were located within 60 meters (200 feet) of each other. The salapkar was a popular destination of the city’s children. They would simply sit on it and then slide down. Then, they would run up the dirt hill that led to the top of the rock and slide down it again. It was commonly believed that the rock had become smoother and more slippery over the years due to heavy use. [6]

Chenkoush, the Koojoolian family, circa 1913. Left to right: Melikset/Mike Koojoolian; his wife, Merijan; his mother, Yeghisapet (seated); his aunt, Khatoun; a child (name unknown); and a woman who is most probably the unidentified child’s mother (name unknown). Mike emigrated to the United States in 1912. His mother, Yeghisapet, died in 1914. All the others in this photograph were killed during the Armenian Genocide. Mike did not appear in the original photograph. He added his image to the original in 1921 or 1922 (Source: Charlotte (Booloodian) Fountinelle. Courtesy of Barlow Der Mugrdechian).

Keri-Keri

The players would split into two teams, each consisting of ten or more players. The game was more enjoyable with a larger number of players. This was a popular game that locals also enjoyed watching.

A horizontal line would be drawn across the middle of a courtyard or a field. Each team would designate a home base in their own territory. Then, the two teams would simultaneously advance from their respective bases to the center of the field and face each other across the line. Upon a signal, the grappling would begin. Each team would seek to force members of the opposing team to their side of the line. Naturally, the struggle would be intense. If a team succeeded in abducting an opponent, its members would call out, “Keri-keri!” The captured player’s teammates could try to help him back to their side, but they could not cross the line. So, if a team captured an opponent, the team members would quickly retreat to their home base, forcing the captive along. Then the two teams would face off across the line again and resume the game.

The team that captured the greatest number of hostages would win the game. [7]

Zunguzung

This was a game played with a ball by two teams. Each team consisted of four players. One team, the bargogh team, would be the “mounts,” and the other team would be the “riders."

The players on the bargogh team would stand in a triangle (if there were three of them) or a square (if there were four), leaving a distance of about three meters (ten feet) between them. The “riders” would then climb onto their shoulders, and would also have the ball. They would throw the ball to each other, while their “mounts,” constantly repeating “Zunguzung,” would move up and down, trying to throw them off their balance. The goal of the “mounts” was to force one of the “riders” to make a mistake and drop the ball to the ground.

The riders would win the game if they achieved a predetermined number of passes with the ball. [8]

Luglug Fight

In the local dialect, luglug meant “stork.” The word was associated with any game played while hopping on one leg. [9]

This game required at least ten players. Two teams would be formed, one attacking (Team A) and the other defending (Team B). A line would be drawn down the middle of the playing field, and each team would take control of its half, where its hel would also be located.

Throughout the game, the players had to remain in the luglug position, meaning they had to hop on one leg. They were allowed to kick each other or strike each other with their elbows. Any player that placed his/her second foot on the ground was immediately eliminated.

The attacking team had to capture the defending team’s hel. This attacking team’s players were also allowed to hop back to their own territory, where they were allowed to place both feet on the ground and rest. Then they would rejoin the game in the luglug position.

Team A would win if any of its players successfully breached Team B’s defenses and “captured” the hel. The defenders had the right to assign one player to remain on the periphery of the hel and defend it. This player, still in the luglug position, would be Team B’s last defense.

The game would end once Team A successfully neutralized all the players of Team B and captured Team B’s hel. But they could also fail. If the players of Team B successfully eliminated the majority of Team A’s players, they could go on the offensive and could capture Team A’s hel. [10]

Luglug-Vazk

This game was played by multiple players. They would stand behind a line, and upon a signal from the referee, they would race to the hel in the luglug position. The first to arrive would capture the hel and win the game. The others would, one at a time, carry the winner on their backs, with the latter calling out, “Bring me a midwife, and I’ll bring you a calf!” [11]

Chigin

This was a competitive game played by two teams, each consisting of at least eight players. The game was more enjoyable with a larger number of players. One team would attack, and the other would defend. Each team would have its own territory, which would also include its hel. The two teams would battle it out in the area between the two territories. The attacking team’s objective was to reach the defenders’ hel and capture it, which they would if any of them physically stepped into it.

The game’s rules were very similar to the rules of luglug fight. But what made chigin unique was the physical stance that players were required to adopt. They had to be barefoot, and each would tuck his/her left leg behind his/her right knee and hold his/her left index toe with his/her right hand. This was the chigin position, which gave the game its name.

To strike their opponents, the players would use their right elbows and left knees. Any player who failed to hold the chigin position was immediately eliminated. However, tired players could return to their team’s base, where they were allowed to assume the natural position and rest.

If a player was knocked to the ground by an opponent, he/she was not eliminated from the game as long as he/she continued to hold on to his/her toe. [12]

Akladj-Makladj

This was a children’s game. First, a mar and a hel would be designated. The players would stand in a circle, with their wrists pressed together and their palms open. The mar would keep an object in his/her hands. Then, the mar would lower his/her closed fist into each of the players’ open palms, repeating “Akladj-makladj” each time. After making several rounds, the mar would eventually drop the object into the hands of one of the other players, and then stop. The player who received the object would immediately separate from the rest and run to the hel. The other players had to chase this player down and catch him/her. If this player reached the hel without being “captured,” he/she would become the mar. On the other hand, if this player was caught, he/she would be eliminated, and the game would continue with the previous mar. [13]

Angadj-Kashoug [Pulling Ears]

At the start of the game, one player would be chosen by lot as the bargogh. This player would stand in front of the others, with his/her back to them. One of the other players would suddenly pull one of his/her ears. Then, all the players except for the bargogh (including the player who pulled the ear) would raise their hands and cry out together, “Who was it?” The bargogh would turn around and guess which player had pulled his/her ear. He/she had only one chance to guess correctly. If the guess was correct, the guilty player would become the bargogh, and the game would restart. Otherwise, the same person would continue acting as the bargogh until he/she guessed correctly. [14]

Kala

This game was played with a ball (top) by two or more players. The ball was made by winding cotton thread. The player had to kick the ball as high as possible, then quickly spin around and catch the ball before it hit the ground. The same action would be repeated until the player reached a predetermined number of catches (100 or more). If the player succeeded in reaching this goal, his/her playmates had to take turns carrying him/her. [15]

Top-Arnoug

This game was played by two players or two teams. The players would split up and throw a ball to each other. The player or team that let the ball drop to the ground would lose a point. At the end of the game, whichever player or team had lost the most points would lose. The players on the losing team would have to carry the winners. [16]

Bahvudouk

This game involved a bargogh and hel. The hel was usually the tombstone in the courtyard of the Chenkoush church, a spot in the school courtyard, or simply a rock or a stone staircase.

The bargogh would have a handkerchief tied around his/her eyes and would stand with one hand resting on the hel. The other players would hide behind pillars, tombstones, staircases, fences, or other objects. Once all these players were hidden, they would simultaneously call out “You!” and the bargogh would untie the handkerchief, open his/her eyes, and try to find the hidden players. Whenever he/she located one, he/or she would call out their name and immediately touch the hel. At that point, the player who had been spotted would become the bargogh and the game would restart. The hiding players could also exploit the fact that the bargogh would sometimes stray too far from the hel. If any of them could reach the hel undetected and touch it, the game would restart with the same bargogh. [17]

Kulla

This game was played by two or more players.

A small hole was dug under a wall, with a diameter and depth of about 25 centimeters. This hole was called the kulla. The courtyard of the Chenkoush church, a favorite playground of the local schoolchildren, was covered in kullas.

One of the players would stand beside the kulla. He/she was its guardian and defender. The second player would stand at a distance of about two meters (six feet) and throw apricot seeds towards the kulla. After throwing the first seed, this player would also have to call out “tak” (odd) or “chout” (even). If he/she succeeded in throwing all the seeds into the kulla, he/she would win. This player would also win if the number of seeds that did not fall into the kulla was odd if he/she had picked odd; and even if he/she had picked even. The guardian of the kulla, if defeated, would owe the winner the same number of seeds as the latter had thrown. [18]

Kdag-Tskoug

This was a group game, played by at least six players. The game was more enjoyable with a larger number of players.

The game featured a mar and a bargogh.

The bargogh would bend at the waist, spread his/her legs, and hold his/her knees with his/her hands. How low the bargogh bent was determined by all the players at the start of the game.

The mar would be the first to leap over the bargogh. He/she would put both hands on the bargogh’s back and jump over the latter. As the mar leapt over, he/she would say, “Morn haram chullar!” and place a hat on the bargogh’s back. Even if the hat fell, the mar was exempt from elimination. He/she could simply pick it back up from the ground and place it on the bargogh’s back.

Then, it would be the other players’ turn to jump. They would have to leap over the bargogh and touch the hat on the latter’s back while in the air. However, the hat could not fall to the ground. Any player that caused the hat to fall would be eliminated immediately. That player would then become the bargogh and the game would restart.

Expert players could make the leap harder for the players who followed them by moving the position of the hat on the bargogh’s back in such a way that it was balanced precariously. But such moves could also backfire. Similarly, an expert player could move the hat to the center of the bargogh’s back, thus helping the next leaper. [19]

Esh-Kani

This was a very popular game in Chenkoush, played by seven players split into two teams (Team A and Team B). Each team would consist of three players, and the game also required a referee, who was called parts.

The parts would stand straight, with his/her back against a wall. The first player on Team A would bend down, place his/her head by the parts’ side, then hold this position. The second player would similarly bend down behind the first player in the same position, and so on, until the entire team formed a long line.

The first player from Team B would run up, place his/her hands on the back of the last player in the line, and leap over and onto the bargogh team. The second player from Team B would do the same, and land behind his/her teammate. The third would do the same, and so on. Once all the players on Team B had successfully landed on the backs of the bargogh players, the parts would ask Team B’s mar (the first to leap), “Eshu kani?” [“How much for the donkey?”]. The mar would reply, “15,” and in one breath count from one to 15. Then the parts would ask the same question to the second player on Team B, who would answer, “20,” then count to 20 in one breath. In other words, each player would have to add five to the previous player’s number and count to it in one breath. The third player would have to count to 25, the fourth to 30, and so on. If all the players on Team B accomplished this task, the turn would once again be the mar’s, who would continue to add five to the last number counted.

The game would end when one of the players on Team B failed to count to the prescribed number in a single breath. At that point, the bargogh players would become the leapers, and vice-versa. [20]

Challig-Chbouk

A challig was a small stick, about 15-20 centimeters in length, with sharpened ends. A chbouk was also a stick, about 80 centimeters in length.

The players would stand behind a line, on which they would arrange their challigs. At an equal distance from this line would be each player’s hel, which was his/her target.

Upon a signal, the players would strike one of the sharp ends of their challigs with their chbouks, launching them into the air. They would then have to continue hitting their challigs and preventing them from falling to the ground, while at the same time advancing towards their hels. The first to reach his/her hel with his/her challig was declared the winner. [21]

Churr

Churr was a type of race. The participants would stand behind a line drawn on the ground, and upon a signal from the referee, run to the hel, which would be located at a distance of 60 to 150 meters (200 to 500 feet) from the line. The first runner to reach the hel would win. [22]

Borkal [Jumping]

In the Chenkoush dialect, borkal meant “to jump.” Six different jumping games were played in Chenkoush:

- Players would take a running start, and upon reaching a line drawn on the ground, take three long steps and then jump forward as far as possible. Basically, a primitive version of triple jump.

- The same game as above, except that players would not take a running start. They would stand behind a line, then take three long steps forward and jump.

- Players would take a running start, and upon reaching a line drawn on the ground, they would jump forward as far as possible. Basically, a primitive version of long jump.

- The same game as above, except that players would not take a running start. They would stand behind a line, then jump forward.

- Players would run in the luglug position from a predetermined distance. Upon reaching a line drawn on the ground, they would take three long hops (while remaining in the luglug position) and then jump forward.

- The same game as above, but the players would not take a running start. They would stand behind a line, take three long hops forward, and then jump forward.

Naturally, in all these games, the player who jumped the furthest was declared the winner. [23]

Achk Gaboug

This game would feature a bargogh, who would stand in the center of a circle consisting of the other players, a handkerchief tied around his/her eyes. The other players would disperse and run around the bargogh while singing the following song:

Achk gabougu lav pan e

Yete deghu shad lan e

Ashkhade indzi prnes

Achkerout gabu kages.

Translation:

Achk gaboug is a great thing,

If the playground is wide,

Make an effort to catch me,

To untie your blindfold.

If the bargogh succeeded in catching one of the other players and guessing his/her identity by feeling his/her face, the captured player would become the bargogh and the game would restart. If the bargogh caught a player but did not identify him/her correctly, the other players would call out, “Wrong, wrong!” and continue to run around the same bargogh, until the latter caught a player and correctly identified him/her. [24]

Tboug

This game was similar to achk gaboug, but was played without blindfolding the bargogh. The bargogh would stand in the center of the circle of players. Suddenly, one of the other players would tag him/her in the shoulder, head, or back, then run away. The bargogh had to immediately catch the player who had tagged him/her before being tagged by another player. If he/she succeeded, the captured player would become the bargogh. If another player tagged the bargogh before the latter could catch the first tagger, the bargogh would have to catch this second player. The players could keep tagging the bargogh until the latter eventually captured one of the taggers. [25]

Koldash

This game was usually played by youth, using a heavy stone.

In Turkish, kol means “arm,” and dash means “stone.” As the name implies, the game was a stone-throwing competition. The players would stand at a predetermined spot and would throw the heavy stone as far as they could. Naturally, whoever threw the stone the furthest was declared the winner. [26]

Vek [Knucklebone] Games

Knucklebone games were very popular in Chenkoush. Each side of a knucklebone had its own name in the local dialect, and these names varied according to the specific game that was being played. For example, in vek kochel, the rough and ear-shaped side of the knucklebone was called zil. This side of the knucklebone was considered favorable. The exact opposite side of the zil, which was flat and considered unfavorable, was called tam. The deep and concave side on the back of the knucklebone was called bord, and the exact opposite side was called grnag. However, in vek tskoug, the zil was called agha, the tam was called esh, the bord was called kogh, and the grnag was called mart. [27]

Vek Kochel

This was a game played by two children. The first player would drop five-ten knucklebones to the ground from a height of about a meter (three to four feet). The second player would give the first player as many knucklebones as the ones that landed on their zil side; and in exchange receive from the first player as many knucklebones as the ones that landed on their tam side. The knucklebones that landed on the bord and grnag sides were discounted. The first player would then collect the initial set of knucklebones and toss them again, repeating this operation until all of them landed either on the zil or tam side. At that point, the two players would switch roles. [28]

Vek Tskoug

This game was played to amuse and entertain children. The child’s father or older brother would call out the child’s name and ask, “What is [child’s name]?” At the same time, he would hold the knucklebone with three fingers (thumb, index finger, and middle finger), then toss it to the ground from a height of a meter (three to four feet). Expert players would often succeed in making the knucklebone land on the desired side. If it landed on the zil side, the father or older brother would answer his own question with, “He/she is an agha,” meaning the child was noble. If it landed on the tam side, the child was said to be an esh [donkey]; if it landed on the bord size, he/she was said to be a kogh [thief]; and if it landed on the grnag side, the child was said to be a mart [person/man]. [29]

Dakka

A dakka was a shot of marble. The players would line up behind a line, crouch down, and each would place his/her dakka in front of him/her. Upon a signal from the referee, they would use regular marbles to strike the dakka and launch it forward. At the end of the game, the player who had advanced his/her dakka the furthest would be declared the winner. [30]

Hamrank

Players would throw a ball at a wall from a predetermined distance, then catch it when it bounced back before it hit the ground. The first player who successfully repeated this operation for a predetermined number of times was declared the winner. [31]

Khubushde (or Klololo)

The players would stand in a circle, then form rings with the thumbs and index fingers of their right hands. The previously designated mar would stand in the center of the circle, then go around and insert his/her middle finger into the rings made by the other players, while repeating “Klololo-klololo!” Whoever succeeded in snaring the mar’s finger in his/her “trap” would become the mar, and the game would restart. [32]

Garmoudj (or Gamourch) [Bridge]

This game was played by a single player or by a group of players. It required a very small ball and five small pebbles. The player would arrange the pebbles on the ground, leaving a gap of about five centimeters between each. Then, he/she would open his/her left hand wide, with the thumb and index finger stretched out, to make a “bridge.” This bridge would be placed right beside the pebbles. The player would throw the ball into the air with the right hand, and he/she had to use the same hand to toss one of the pebbles under and through the “bridge,” then catch the ball before it fell to the ground. The same operation was repeated until all five pebbles were thrown under the bridge. Each tossed pebble had to remain clear of the other pebbles already on the other side of the bridge. [33]

Goulla or Gyulla [Marbles]

This was an individual or group game, played with colorful marbles. The players would arrange several marbles about 1 to 1.2 meters (three to four feet) from a predetermined line, then strike a slightly larger marble with the thumb to launch it towards the smaller marbles, with the aim of hitting them. [34]

Hinkkar [Five Rocks]

The player would arrange five small rocks on the ground. Then he/she would throw a ball into the air with the right hand. He/she had to pick up one of the rocks from the ground with his/her left hand, and with the right hand catch the ball before it hit the ground. The same process was repeated until the player picked up all five rocks. [35]

Chvan Borkal (Skipping Rope)

This was a very popular game in Chenkoush, primarily played by young girls. The player would hold both ends of a rope, then swing it over her head and jump over it with both feet. The rope would swing below her feet, and she would continue skipping. The game could be played alone or with another player, in the form of a contest. [36]

Chzuldouk

This was the game of seesaw. A log was fastened to a stump with a height of about a meter (three feet). A child would sit at each end of the log, and they would alternately push each other up, chanting “Chuz-chuz.” [37]

Damblapsdig

This game was similar to chzuldouk. A log was fastened to a stump in the same way, but in the case of damblapsdig, the game would often end in a physical altercation, especially if the child sitting on one end of the stump decided to put all the pressure he/she could on his/her side, and not allow the other player to get back down, or even causing him/her to fall off the log. [38]

Dashaghkar

The players (two or more) would crouch in a single line, their hands on the ground and their heads raised. Each player would hold one end of a string between his/her teeth. At the other end would be a small pebble. The referee would count from one to five, and during that time, the players would bob their heads up and down, causing the string and the pebble to whirl about. Upon the referee calling out the number five, the players would all release their pebbles. The winner was the player who tossed his pebble the furthest. Often, inexperienced players, while bobbing their heads up and down, would strike their own faces with the pebble, causing cries of pain and tears. There were two methods of tossing the dashaghkar – simply tossing it forward, or backwards over the head. [39]

Kar Aveltsnoug

This was a favorite game of local adolescents, played by two or more players.

One player would take three steps forward from a line and place a rock on the ground at that spot. The next player would do the same, taking three steps forward from the line and reaching the rock. Then, this player would stand on one leg, pick up the rock with one hand, and move it to a spot further ahead. This act of advancing the rock was called “kar aveltsnoug.” The same player would have to hop back to the starting line on one leg. Then, a third player would repeat the same operation. The game would end once the rock became unreachable to the players. [40]

Kar Nedoug [Throwing Rocks]

A player would throw a rock of medium size from a predetermined spot by standing with his/her legs spread, bending all the way down so that his/her head almost touched his/her knee, spinning the rock several times over his/her head, then throwing it as hard as he/she could backwards through the legs. The player who threw the rock the furthest would win the game. [41]

Dama [Checkers]

This was a favorite game of the elderly in Chenkoush. It was usually played in the cemetery. The two players would sit facing each other across a tombstone. They would then draw the checkers board, which consisted of 64 squares, on the tombstone, and arrange their pieces on the grid. Checkers was also played by many young people. [42]

Mour-Ksoug

This was an enjoyable game played at home with guests. One of the guests or family members would be given a plate, the bottom of which would be rubbed with black soot. Another player would hold a clean plate and would address the first player thus: “Now, you must do everything I do.” He/she would then rub the bottom of the clean plate with his/her index finger, and then use the same finger to draw imaginary lines on his/her face. The first player would have to do the same, which would result in black lines appearing across his/her face, eliciting the amusement of the attendees. [43]

Tavli (Backgammon) and Card Games

Tavli (backgammon) and card games (iskenbil) were popular games played in the homes of Chenkoush. They were also played in the cemetery during Easter celebrations. [44]

Tak-Chout (Odd-Even)

This was a game played by two or more children. One of them would hold a bunch of small items (raisins, almonds, seeds, etc.) in the palm of his/her hand, then hold his/her closed fist out and ask the other player, “Tak or chouk?” The other player would prod the skin of the first player’s wrist with his/her index finger and thumb and try to guess whether the first player had an odd (tak) or even (chout) number of objects in his/her palm. If the second player guessed correctly, he/she would win the “fortune” concealed in the first player’s hand. [45]

Kite Flying

This was a popular activity among the children of Chenkoush. The kites were usually made by older family members or older brothers. The kites were saucer-shaped and made of pieces of paper that were glued to circular or rounded sticks of wood or tin wire. [46]

- [1] Karnig Kevorkian, Chenkoushabadoum [History of Chenkoush], first volume, S. Hagopyants Press, Jerusalem, 1970, pp. 414-415.

- [2] Ibid., pp. 423-424.

- [3] Ibid., p. 425.

- [4] Ibid., pp. 426-427.

- [5] Ibid., p. 427.

- [6] Ibid., p. 418.

- [7] Ibid., pp. 419-420.

- [8] Ibid., p. 427.

- [9] Ibid., p. 421.

- [10] Ibid., pp. 421-422.

- [11] Ibid., p. 422.

- [12] Ibid., pp. 424-425.

- [13] Ibid., pp. 414-415.

- [14] Ibid., p. 415.

- [15] Ibid., p. 416.

- [16] Ibid.

- [17] Ibid., p. 417.

- [18] Ibid., p. 420.

- [19] Ibid., pp. 420-421.

- [20] Ibid., p. 421.

- [21] Ibid., p. 423.

- [22] Ibid.

- [23] Ibid., p. 424.

- [24] Ibid., p. 415.

- [25] Ibid.

- [26] Ibid., pp. 425-426.

- [27] Ibid., p. 418.

- [28] Ibid.

- [29] Ibid., pp. 418-419.

- [30] Ibid., p. 419.

- [31] Ibid., p. 416.

- [32] Ibid.

- [33] Ibid.

- [34] Ibid.

- [35] Ibid., pp. 416-417.

- [36] Ibid., p. 417.

- [37] Ibid.

- [38] Ibid., p. 419.

- [39] Ibid.

- [40] Ibid., p. 426.

- [41] Ibid.

- [42] Ibid., pp. 427-428.

- [43] Ibid., pp. 428-429.

- [44] Ibid., p. 429.

- [45] Ibid., p. 415.

- [46] Ibid., pp. 415-416.