Kaza of Shirvan - Monasteries, churches and places of pilgrimage

Author: Tigran Martirosyan, 31/10/2023 (Last modified: 31/10/2023)

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the territory of the Sgherd (Siirt) sandjak (prefecture) of the vilayet (province) of Bitlis, of which Shirvan formed part as a kaza (county), was placed under the jurisdiction of the Sgherd Prelacy of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople. [1] In the years before the genocide in 1915, archimandrite Paren Melkonian, in 1904, [2] and archimandrite Koryun Srapian, in 1908, [3] were the prelates of Sgherd. Until 1805, Sgherd was a bishopric under the jurisdiction of the John the Baptist (Surb Karapet) monastery in Moush. However, afterwards it was decided to move the prelates and the clergy to the town of Sgherd (Siirt), the administrative center of the same name as the sandjak. From the second quarter of the nineteenth century until 1865, the Sgherd Prelacy’s jurisdiction extended over Sgherd (the central kaza of the same name as the sandjak), Shirvan, and Kharzan, and included several counties in the prefectures that lay beyond the sandjak of Sgherd. [4]

The current names of the Armenian-populated villages shown on the map are mentioned between brackets.

Avav [Gürgencik], Avin [Kayalı], Baytaroun [İkizler], Berk [Yatağan], Daraban [Dokuzçavuş], Deravel [Yarımtepe], Derik [possibly Kayahisar], Derik [possibly Söbetaş], Derzni [Adakale], Djouma [Kaval], Gndzik [Oya], Gondegizan [Suludere], Gorinan [other known names Gurena, Gorihan], Karve [Taşlı], Kelin [Durankaya], Kevidjan [Yolbaşı], Khandak [İncecik], Kigan [İkizler], Kyosakh [İncesırt], Kyufra [Şirvan], Madan [Madenköy], Matar [Sarıtepe], Mazoran [Özdoğan], Merdj [Suluyazı], Minar [Dilektepe], Mzre [Aktay], Nebayn [Turgutlu], Poukh [Köprü], Sematar [current name unknown], Sermet [possibly Yamaç], Serous [Kesmetaş], Shmelia [Sıvacık], Siserk [Çayır], Smkhor [Sarıdana] , Sorian [Koyacık], Zvzik [Dişlinar].

Because in the fifth and sixth centuries AD, the Sassanid dynasty that ruled the Persian Empire pursued discriminatory religious practices against the Armenian Apostolic Church, segments of Armenian populations inhabiting several southern and south-western gavars (cantons) of the Kingdom of Greater Armenia converted to Nestorian Christianity, also known as Nestorianism. Consequently, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the remnants of “Nestorian Armenians” were found in several villages throughout the kaza of Shirvan. [5] By the turn of the twentieth century, Shirvan was an underdeveloped and economically and socially backward county. While the Armenian church agencies and community organizations which fostered education in Armenian populated areas of the Ottoman Empire had a large network of village schools, mostly at local churches, in Shirvan schools were virtually non-existent [6] and the number of churches was small.

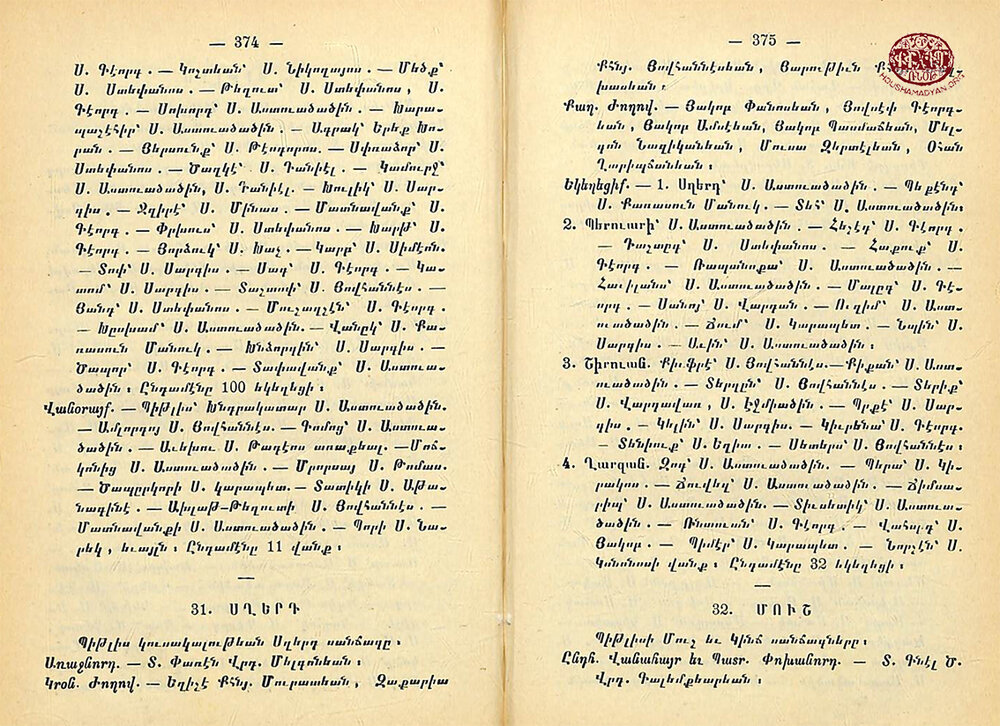

The 1904 Comprehensive Calendar of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital, published in Constantinople, placed the total number of Armenian churches in the Sgherd sandjak at 32. [7] According to Archbishop Malachia Ormanian, the Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople from 1896 to 1908, in the early 1900s, there were 33 churches under the jurisdiction of the Sgherd Prelacy, which extended over Sgherd (the central homonymous kaza), Shirvan, Kharzan, and other counties within the Sgherd prefecture. The number of adherents to the Armenian Apostolic Church for the Sgherd sandjak was placed by Ormanian at 25,000, while the sandjak’s Catholic Armenians totaled 500. [8] In 1900, an editorial in the periodical Byurakn published in Constantinople, counted several Catholic churches in Sgherd, as well as from 40 to 45 Protestant Armenians attending a sole preaching house. [9]

According to the editorial “Hayastanyayc yekeghecin Tachkastanoum” (The Armenian Church in Turkey), published in Ararat, the journal of the Mother See of the Armenian Apostolic Church published in Etchmiadzin, in 1895, during the Hamidian massacres, several monasteries and churches in about 20 Armenian populated villages of Shirvan, among them Serous [Kesmetaş], Avin [Kayalı], Avav [Gürgencik], Nebayn [Turgutlu], Sermet [possibly Yamaç], and Siserk [Çayır], were razed to the ground and some of the Armenian clergymen forcefully Islamized. The remaining Armenian monasteries and churches have been converted to mosques where the Turk mollahs triumphantly preached the dogmas of Islam. [10] At the time of British Vice-Consul in Bitlis James Henry Monahan’s visit to Shirvan in 1898, whose purpose was to gather information that could shed light on the atrocities and iniquities perpetrated by the Kurds, the Armenians, as well as local Syriacs, “had been almost all reconverted” to Christianity. [11]

In 1902, the statistical report prepared by the Sgherd Prelacy counted one monastery and 19 (based on other estimates, 21) churches in Shirvan. [12] For unknown reason, the census carried out by the Patriarchate in 1913-1914, the tabulated results of which are held at the Bibliothèque Nubar de l’UGAB in Paris, produced no figures for Armenian monasteries and churches in Shirvan. [13] The updated Patriarchate census data available to Kévorkian & Paboudjian placed the number of churches in Shirvan in 1914 at nine. [14] The sole-authored treatise written by Kévorkian, who apparently upgraded the Patriarchate figures using supplementary census data available to him, identified 11 churches in Shirvan prior to 1915. [15]

A sizeable portion of Christian village populations in Shirvan were Orthodox Syriac. Because a segment of these Syriacs was Armenian speaking, their ethnic origin was not always recognized in the Armenian sources of the time. [16] A Syriac priest, whom Irish geographer Henry Lynch met during his short sojourn in Bitlis in the late-1890s, concurred that “some Syriacs had emigrated, while the greater number had become Armenians.” When Lynch enquired “why the faithful remnant spoke Armenian to the exclusion of any Syriac dialect,” the priest replied, “because this earth is Hayasdan [Armenia].” He added that there were some 1,500 Syriacs in the sandjak of Sgherd, mostly in the kazas of Sgherd and Shirvan. Their spiritual leader was the Patriarch of Mardin, [17] a historical city of Mtsbin in the so-called “Armenian Mesopotamia,” now in southeastern Turkey.

At the same time, the reverse process of Assyrianization of the Armenians living in the southern parts of the Armenian Plateau, such as Shirvan, was not uncommon. In his work “Amitayi ardzaganqnerou verakochumn” (The Renaming of the Echoes of Amita), Armenian writer Tigran Mkound mentioned an Armenian Gospel Book written in Syriac letters that existed in the areas populated by these two ethnic and religious groups. The Gospel Book was most likely intended for those assimilating Armenians who had not yet lost their native language. The fact that there were no significant theological differences between the Armenian Apostolic and Jacobite Syrian churches had played a notable role in the Assyrianization of the Armenians, including segments of the inhabitants of Shirvan. In fact, the Ottoman state formally considered the Jacobite Syriacs as forming part of the Armenian millet, [18] placing their church and its adherents under the jurisdiction of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople. [19]

Nowadays in Shirvan, near the modern-day village of İncekaya, whose former name was Körmaş or Kürmas, 20 kilometers northeast of Sgherd (Siirt), stands a chateau-like fortress, called the Körmaş fortress after the village’s name. This medieval fortress is believed to have been built by the Byzantines who owned the area after Western Armenia fell under Byzantine rule, but in the eleventh century was captured by the Seljuk Turks intruding into the area from the steppes of Central Asia. The magnificent fortress housed residential rooms, a bath, cellars for food storage, as well as a small cozy church.

This study relied on several primary sources which are enumerated in the list below. Tadevos Hakobyan, Stepan Melik-Bakhshyan, and Hovhannes Barseghyan, the authors of the “Dictionary of Toponymy of Armenia and Adjacent Territories,” the travel guide published in 1884 by Manuel Mirakhorian, an Armenian school inspector who traveled extensively across Western Armenian provinces, British Vice-Consul James Henry Monahan’s travel report, who journeyed to Shirvan in 1898 and visited all the Christian villages of the county except four small ones, the 1904 and 1908 Comprehensive Calendars of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital in Constantinople, Raymond Kévorkian’s sole-authored treatise on the history of the Armenian Genocide published in 2012, the periodical Byurakn, and the journal Ararat, provided additional data.

- The travel report by Aristakes Tevkants, an Armenian folklorist who journeyed to Western Armenia in 1878;

- The Statistical Report prepared by the Sgherd Prelacy in 1902;

- Supplementary data from the 1913-1914 Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople census available to Kévorkian & Paboudjian (1992); and

- The book about the sufferings of the Armenian clergy during the genocide composed by writer Teotoros Lapjinchian (Teodik) in 1921; [20]

Below is a list of monasteries, churches, and places of pilgrimage in the kaza of Shirvan during the late Ottoman era. Wherever possible, the list includes information regarding the number and known names of the serving clergy, which were extracted from Teodik’s work, the 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report, the 1913-1914 Patriarchate census held at the Bibliothèque Nubar de l’UGAB in Paris, and the testimony of a genocide survivor from the village of Gndzik [Oya]. Unless otherwise mentioned, the information submitted below is drawn from sources covering a period of almost 40 years or from 1878 to 1915. The current Turkified names and geographical coordinates of the towns and villages in Shirvan, where Armenian monasteries, churches, and places of pilgrimage were located, can be found in the article “Kaza of Shirvan—Demography”

Monasteries of the Shirvan county

Because Shirvan remained certain terra incognita throughout most of the period covered by this study, most sources used for it reported no Armenian monasteries in the county. One exception is the 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report which identified one unnamed monastery at the village of Matar (present-day Sarıtepe) and one church at Sematar (current village name unknown) that served as a monastery. Another exception is the article “Sgherd” appearing in Byurakn, a periodical published in 1900 in Constantinople, whose author placed the Holy Cross (Surb Khatch) monastery, which he described as a “famous edifice”, in Shirvan. [21] It is known, however, that the Surb Khatch monastery was situated in the village group of Mamrtank that formed part of the neighboring kaza of Khizan (Hizan) in the vilayet of Bitlis, just west of the Armenian populated village of Segh. [22] Apparently, the site of this monastery was so famous that the residents of adjacent villages of Shirvan went there, likely on pilgrimages or for veneration.

Monastery of Saint Joseph (Surb Hovsep) at Matar

Also called Surb Hovsepa vank, the monastery was located 15 kilometers (9 miles) northwest of Sgherd (Siirt). [23] The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report indicated that the monastery was in ruins at the turn of the twentieth century.

Monastery (church) of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin) at Sematar

The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that at the turn of the twentieth century, this village church, which had served as a monastery, was half-ruined.

Seghavank (Segha vank) or Holy Cross (Surb Khatch) monastery

Seghavank was also known under the name of Derzhkou (Dershkou) Holy Mother of God Monastery (Derzhkou Surb Astvatsatsni vank). In 1895, during the Hamidian massacres, the Kurds converted the Surb Khatch monastery to a mosque. [24]

Khndrakatar Holy Mother of God Monastery (Khndrakatar Surb Astvatsatsni vank)

Another monastery that lay close to the adjacent villages of the kaza of Shirvan, which their inhabitants visited, was the Khndrakatar Surb Astvatsatsni monastery located near the Armenian populated village of Amp or Amb (present-day Çalıdüzü) [25] in the central part of the vilayet of Bitlis (in Turkish, Bitlis Merkez). According to Hamazasp Voskian, the author of the treatise on the Vaspourakan-Van monasteries, the year when the monastery was built is difficult to determine. Most likely, the construction dates to the late-eighteenth century. [26]

Churches of the Shirvan county

Avav

The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that at the turn of the twentieth century an unnamed church in the village stood in ruins. Hakobyan et al. suggested that the religious edifice that the village housed was the Church of Saint Thomas (Surb Tovmas).

Avin

Tevkants in 1878 and Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report in 1902 reported the Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin). The church was a neat and arched structure and at the turn of the twentieth century was intact. However, the supplementary Patriarchate census data and Hakobyan et al. identified the Church of Saint Simon (Surb Shmavon) in the village.

Baytaroun

The Church of Holy Resurrection (Surb Harutyun). The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that at the turn of the twentieth century the church was still intact, albeit partly ruined.

Berk

The Church of Saint Sargis (Surb Sargis). Monahan reported that in 1895, the Kurdish sheikh of Zerfo and his men pillaged all the fourteen Christian houses, except that of the village headman which was protected by a friendly Kurd. The church was sacked and as of 1898 was still in ruins. [27] The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that the church was a splendid structure built of stone and, at the turn of the twentieth century, was still intact.

Daraban

The Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin). The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that the church was in ruins. Elsewhere in the Prelacy lists, Daraban is mentioned as a locality that housed three churches which at the turn of the twentieth century were already in ruins. [28]

Deravel

Kévorkian & Paboudjian identified the Church of Saint Shmavon (Surb Shmavon) in the village. [29]

Derik

This village of Derik (present-day possibly Kayahisar), a locality in the village group of Eroun, is not to be confused with the homonymous village in Shirvan Central (in Turkish, Şirvan Merkez) below. This village of Derik, until the beginning of the twentieth century, housed the Church of Surb Vardavar, otherwise known as the Church of Surb Etchmiadzin. [30] The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that there were ancient manuscripts kept at the church and that the oldest of the carved cross-stones khachkars standing near the church gates dated back to 1060 and 1071. Monahan reported that, as of 1898, the church remained and was used as a straw store. A few Armenian families, though they all were forcibly given Muslim names, practiced the Christian religion in their houses and used their Christian names when there were no Muslims around. In 1895, an Armenian priest from a neighboring village, possibly Avin (present-day Kayalı), serviced the church on demand. [31]

Derik

This village of Derik (present-day possibly Söbetaş), located in Shirvan Central (in Turkish, Şirvan Merkez), is not to be confused with the homonymous settlement in the village group of Eroun above. This village of Derik reportedly housed the Church of Surb Yeghishé.

Derzni

The Church of Saint John (Surb Hovhannes). The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that the church was an elegantly built, splendid structure complete with four apses and, at the turn of the twentieth century, was still intact. Hakobyan et al. reported that before 1886 ancient manuscripts were kept at the church, which were destroyed due to the poor storage conditions. Slightly to the north of the village stood an ancient crumbling fortress with a ruin of a monastery nearby.

Djouma

Tevkants reported the Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin) in 1878. However, the 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report identified the Church of Saint John the Baptist (Surb Karapet) which at the turn of the twentieth century stood intact.

Gndzik

The Church of Saint Stephen (Surb Stepanos). The church had several hand-written Gospel Books. It is in this church that, according to genocide survivor Berkho Azoyan, a British Consul who visited the village several years before the genocide, snitched an ancient church bull, called kondak in Armenian, that bore the image of the Virgin Mary. [32] The visiting consular official’s name can only be guessed. It is known that P.J.C. McGregor was the British Consul in Erzurum from 1910 to 1912. William Beauchamp Heard was the British Vice Consul in Bitlis from 1907 to 1908. One serving clergyman, Father Gorgiz. In the graveyard near the Surb Stepanos church stood a large tombstone bearing cuneiform inscriptions. [33]

Gondegizan

Monahan reported that, as of 1898, the inhabitants of Gondegizan had no church or priest and were only visited once a year by the Jacobite bishop of Bitlis. In 1895, upon demand from neighboring Kurds, the villagers all were forced to declare themselves Muslims and remained in the profession of Islam for seven months till the summer of 1896 when they all returned to Christianity. [34]

Gorinan

Tevkants reported the Church of Saint James (Surb Hakob) in 1878. However, the supplementary Patriarchate census data and Teodik identified the Church of Saint George (Surb Gevorg). One serving clergyman, Father Arsen Muradian. The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that Surb Gevorg was a splendid church complete with three apses. According to Monahan, in 1898, after the violence during the Hamidian massacres diminished, the Christian inhabitants were practicing their religion freely, having a church and priest in their village. [35]

Karve

Tevkants reported three unnamed churches in 1878.

Kelin

The Church of Saint Sargis (Surb Sargis). The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that the church was built of stone, only the arch was made of wood, and at the turn of the twentieth century was still intact.

Khandak

One unnamed ruined church in the village center. The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report identified another church a little farther from the village, the Church of Saint Cyricus (Surb Kirakos) which stood in ruins.

Kigan

The Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin). One serving clergyman, Father Hakob Ter-Hakobian who, according to Teodik, happened to be in the Khndrakatar monastery during the genocide. [36] The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that the church was ancient, built in a somewhat Syriac style and at the turn of the twentieth century stood intact. The second serving clergyman, Father Barsegh, had to flee to Bitlis during the massacres in Shirvan in 1895.

Kyufra

The Church of Saint John (Surb Hovhannes). The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that the church was half ruined and out of use․ The church was last renovated in 1747. To the north of the village there were ruins of an ancient fortress near which there was another church which the local Muslim inhabitants used as a mosque.

Madan

Tevkants reported the Church of Saint George (Surb Gevorg) in 1878. Jacobite Syriac village. The people of Maden escaped from the need to declare themselves Muslims. Monahan reported that the church was in fairly good repair, but the village had not been visited by a priest since 1895 and the infants were unbaptized, and the dead were buried without any religious ceremony. [37]

Nebayn

Tevkants reported the Church of Saint George (Surb Gevorg) in 1878. However, the 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report identified the Church of Saint Sargis (Surb Sargis), an arched structure which stood intact at the turn of the twentieth century. There were several ancient manuscript Gospel Books kept at the church.

Poukh

Hakobyan et al. reported the Church of Saint Cyricus (Surb Kirakos).

Sematar

The Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin). The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that at the turn of the twentieth century the church was half ruined.

Sermet

The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that an unnamed church in the village stood in ruins at the turn of the twentieth century. Hakobyan et al. suggested that the village church was the Church of Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin).

Serous

Tevkants reported the Church of Saint Toukhmanuk (Surb Toukhmanuk) in 1878. Hakobyan et al. suggested that there were two churches in the village: the Church of Saint George (Surb Gevorg) and the Church of Saint Elias (Surb Yeghia).

Shmelia

The Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin). The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that the church was neat and small, and at the turn of the twentieth century stood half intact.

Siserk

The Church of Saint John (Surb Hovhannes). The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that the church was neat and beautiful and at the turn of the twentieth century stood intact. Hakobyan et al. identified the religious edifice in the village as the Church of Saint Simon (Surb Shamuneh).

Smkhor

The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report identified two unnamed churches in the village. One was in ruins, and the other one, which stood intact, was passed to local Syriacs.

Places of pilgrimage in the Shirvan county

Surb Hovsepa monastery at Matar

The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that the monastery, which was in ruins at the turn of the twentieth century, was a pilgrimage site.

Khndrakatar Surb Astvatsatsni monastery

The monastery stood outside of Shirvan, in the neighboring kaza of Khlat. However, the monastery was considered a famous pilgrimage site by the villagers of Shirvan. They went there on an annual pilgrimage on a specific date, the feast of Hambardzoum (Ascension). [38]

Church of Surb Vardavar or Surb Etchmiadzin at Derik

The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report indicated that the church was a famous pilgrimage site.

Church of Surb Toukhmanuk at Serous

There was a pilgrimage site at or near the church which was venerated by Shirvan villagers. [39]

- [1] Mirakhorian, Manuel. Nkaragrakan oughevorutioun i hayabnak gavars Arevelian Tachkastani [A Descriptive Journey to Armenian-populated Regions of Eastern Turkey]. Constantinople: Partizpanian Publishing House, 1884, Vol. 1, p. 75.

- [2] 1904 Entardzak Oratsouyts S. Prkchian Hivandanoci Hayots [The 1904 Comprehensive Calendar of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital]. Constantinople։ H. Matevosian Publishing House, p. 374.

- [3] 1908 Entardzak Oratsouyts S. Prkchian Hivandanoci Hayots [The 1908 Comprehensive Calendar of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital], Constantinople։ H. Matevosian Publishing House, p. 249.

- [4] The 1908 Comprehensive Calendar of Holy Savior Hospital, p. 315.

- [5] Badalyan, Gegham. “Arevmtian Hayastani patmajoghovrdagrakan nkaragire Mets Yegherni nakhorein (mas VII-rd)” [A Historico-demographic Description of Western Armenia on the Eve of the Armenian Genocide, Part VII: The South-eastern Counties of the Province of Bitlis], Vem, No. 4 (56), 2016, p. 21.

- [6] Verheij, Jelle. “‘The year of the firman’: The 1895 Massacres in Hizan and Şirvan (Bitlis vilayet),” Études arméniennes contemporaines 10 (2018), p. 132.

- [7] The 1904 Comprehensive Calendar of Holy Savior Hospital, p. 375.

- [8] Ormanian, Malachia. Hayots Yekeghecin yev ir patmoutiune, vardapetoutiune, varchoutiune, barekargoutiune, araroghoutiune, grakanoutiune ou nerka kacoutiune [The Church of Armenia: Her History, Doctrine, Rule, Discipline, Liturgy, Literature, and Existing Condition]. Constantinople: V. & H. Ter-Nersessian Publishing House, 1911, pp. 261-262.

- [9] Byurakn, No. 19-20, May 16, 1900.

- [10] Ararat, No. 2 (29), February 1896, p. 89.

- [11] Monahan, James Henry. Report on a Journey in the Cazas Sherwan, Sairt, and Aroh, May and June 1898. London: The National Archives of the United Kingdom, open access at www.jelleverheij.net/sources/1891---1900/journey-in-sherwan/, p. 159v.

- [12] Vichakagrutioun Sgherdi yev ir Temeroun [The Statistics of Sgherd and its Dioceses]. Sgherd Prelacy of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, 1902 (Shirvan kaza chapter), Sheets 6-8.

- [13] The 1913-1914 Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople census. Paris: Bibliothèque Nubar de l’UGAB, p. 78.

- [14] Kévorkian, Raymond, and Paul Paboudjian. Les Arméniens dans l’Empire Ottoman à la veille du genocide. Paris: ARHIS, 1992, p. 506.

- [15] Kévorkian, Raymond. The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London: A.R. Mowbray, 2012, p. 277.

- [16] Verheij, “’The year of the firman’”, p. 129.

- [17] Lynch, H.F.B. Armenia: Travels and Studies, Vol. 2: The Turkish Provinces. London; New York: Longmans, Green, & Co., 1901, p. 153.

- [18] In the Ottoman Empire, the term referred to a non-Muslim religious community.

- [19] Maloyan, Arman. “Dardzial asoracats hayeri masin” [Revisiting the Question of the Assyrianized Armenians], in Armenia and Oriental Christian Civilization, Part II: Papers and Abstracts. Yerevan: Gitutiun Publishing House, 2017, p. 173.

- [20] Lapjinchian, Teotoros (Teodik). Koghkota Trqahye Hogevorakanoutyan yev ir Hotin Aghetali 1915 Tariin [The Calvary of Ottoman Armenian Clergy and its Flock’s Catastrophic Year of 1915]. Tehran: S.N., 2014, pp. 129-131.

- [21] Byurakn, No. 19-20, May 16, 1900, p. 299.

- [22] The exact location of this village is unknown, possibly near present-day Dayılar at 38° 2'53.91"N, 42°35'49.89"E.

- [23] Hakobyan, Tadevos, Stepan Melik-Bakhshyan, and Hovhannes Barseghyan. Hayastani ev harakits shrjanneri teghanounneri bararan [Dictionary of Toponymy of Armenia and Adjacent Territories], Vol. 3. Yerevan: Yerevan State University Press, 1986-2001, p. 446.

- [24] Ararat, No. 2 (29), February 1896, p. 90.

- [25] The village was located at or near 38°19'19.29"N, 42° 5'44.91"E.

- [26] Voskian, Hamazasp. Vaspourakan Vani vanqere [The Vaspourakan-Van Monasteries], Vol. 3. Vienna: Mkhitarian Press, 1947, pp. 924-925, 928.

- [27] Monahan, Report on a Journey in the Cazas Sherwan, Sairt, and Aroh, p. 183.

- [28] Sgherd Prelacy, The Statistics of Sgherd and its Dioceses, 1902, sheet 8, No. 7.

- [29] Kévorkian & Paboudjian, Les Arméniens dans l’Empire Ottoman, p. 506.

- [30] Sgherd Prelacy, The Statistics of Sgherd and its Dioceses, 1902, sheet 8, No. 5.

- [31] Monahan, Report on a Journey in the Cazas Sherwan, Sairt, and Aroh, pp. 171v, 172.

- [32] Testimony of Berkho Azoyan made on August 15, 1916, in Virabyan, Amatuni, ed., Hayots ceghaspanutyune Osmanyan Turqiayum. Verapratsneri vkayutiounner [Armenian Genocide in Ottoman Turkey: The Testimony of Survivors], Vol. 2: The Bitlis Province. Yerevan: Zangak-97, 2012, Doc. 76, pp. 117-118.

- [33] Virabyan, Amatuni, ed., Vshtapatoum. Hayoc mets yegherne akanatesneri achqerov [Vshtapatoum: Armenian Genocide through the Eyes of Witnesses]. Yerevan: Zangak-97, 2005, Vol. 1, p. 320.

- [34] Monahan, Report on a Journey in the Cazas Sherwan, Sairt, and Aroh, p. 195v.

- [35] Monahan, Report on a Journey in the Cazas Sherwan, Sairt, and Aroh, p. 181v.

- [36] Teodik, The Calvary of Ottoman Armenian Clergy, p. 132.

- [37] Monahan, Report on a Journey in the Cazas Sherwan, Sairt, and Aroh, p. 177.

- [38] Voskian, The Vaspourakan-Van Monasteries, Vol. 3, p. 937.

- [39] Badalyan, A Historico-demographic Description of Western Armenia, p. 26.